The three pillars of China’s booming start-up ecosystem

Once known as the “world’s factory”, China has risen to become an economic superpower in recent decades. In fact, the nation is expected to become the world’s largest economy in 2027 in terms of nominal GDP.

Aside from its sheer size, China has successfully transformed its economy from manufacturing towards nurturing an environment to enable high-tech innovations: It is home to more than 150 unicorns, leading the world in the field of AI, robotics and computer vision, to name just a few.

This start-up scene wasn’t built overnight, but through decades of efforts by the Chinese government, state-owned enterprises, large corporations, universities and many more stakeholders. Here is a breakdown of the secret ingredients that have made China a tech powerhouse, through the lens of the World Economic Forum’s own community of trailblazing start-ups, this year’s cohort of the Technology Pioneers.

1. Innovation-friendly policies

The Chinese government played a crucial role in laying out foundations for innovation. In 1978, Chinese leader Deng Xiaoping lured foreign investments and capital with the Open Door Policy, aimed to encourage foreign businesses to set up offices and do business in China.

Alongside this policy, the government also created Special Economic Zones in four different regions, including Shenzhen, to further attract foreign business. The resulting urban growth allowed these cities to position themselves as attractive start-up hubs for the 21st century.

The government also created the Chinese Government Guidance Funds to facilitate public-private investment. These funds – collaborations between central, provincial and local government – focus on investment into industries with emerging and high-potential technologies, including AI and robotics, as well as the digital transformation of traditional industries.

China’s next five-year plan has highlighted industrial internet and domestic industrial software as key focus areas for government policy. As a result, regional governments are rolling out plans, supported by billions in capital for subsidy schemes, trying to encourage small to large factories to undergo digitalization.

“Digital transformation is one of the key targets that all governmental organisations must push to meet in the latest five-year plan. On the entrepreneur side, government has rolled out tax and incubation policies that make it much easier to launch start-ups and accelerate their growth,” said Yuxiang Zhou, CEO of Black Lake Technologies, a tech-driven platform for factories.

2. Academia and industry collaboration

Zhongguancun, China’s Silicon Valley, emerged as a hotbed of innovation due to the Open Door Policy. Located in north-west Beijing, the district has been known as “Electronics Avenue” since the 80s, eventually becoming the Zhongguancun Science and Technology Zone.

Lenovo emerged from Chinese Academy of Sciences, and global tech giants including Google, Intel, AMD and Oracle built their Chinese headquarters and research centres here. More than 20,000 high-tech enterprises and start-ups and nearly half of China’s unicorn companies are based in the district, benefiting from an annual growth rate of over 25% in the last decade .

Zhongguancun’s success stems from an abundance of high-tech talent flowing from academic institutions, such as Peking University, Tsinghua University and Chinese Academy of Sciences, strongly equipped with the start-up mindset. A good example in practice is Tsinghua Holdings, a university-owned entity that fosters the ecosystem in which academia, industry and research collaborate. It has commercialized 56 national key scientific achievements and contributed to over 62 key technologies.

On the industry side, it is nearly impossible to imagine the Chinese start-up scene without BAT (Baidu, Alibaba, Tencent), the Chinese version of FAMGA. According to a report by The Economist, about 80% of Chinese start-ups received investment from BAT companies by the time they reach $5 billion in valuation.

“Getting funded by Baidu Ventures, who truly believe in the strength of AI technology, opened the doors to other great opportunities and added further credibility to our name. Within three months after Baidu’s investment in us, we have received funding from two other investors, and our valuation has doubled,” said Yili Wu, CEO of Sandstar, an AI platform that provides computer vision technology to the retail industry.

It is interesting to note, though, that these Chinese tech giants tend not to invest in the same start-up. This forces start-ups to choose which side they will be on at an early stage, potentially impacting their long-term growth trajectory and direction.

3. Market size, speed and culture

With a population of 1.5 billion, the domestic market is big enough for Chinese start-ups to not have to immediately expand internationally, unlike in a small country like Israel. Once an entrepreneur manages to position the company on the leaderboard within China, the amount of capital and support that can be attracted is huge, further fueling growth.

On the minus side, start-up founders need to be mindful of hundreds of competitors striving towards the same goal. The 996 working hour system – the practice where employees work from 09.00 to 21.00, six days a week – is one sign of this intense environment.

“The size and accessibility of the large Chinese market provides attractive scale and opportunity. For example, there are over 200 million school-age students in China, compared to 50 million in the US, providing unique opportunities for start-ups in the education sector to scale very quickly.

On the other hand, the Chinese start-up culture is hyper-competitive and fast, meaning it is vital to offer differentiation while being agile,” said Guan Wang, CEO of Learnable, providing interactive and artificial intelligence AI solutions for education, finance, manufacturing and public services.

This is also partly what fuels the rapid maturation of Chinese start-ups. For instance, Nio (automobile manufacture) and Ke.com (a real estate platform) both completed their initial public offering on NASDAQ within just five years.

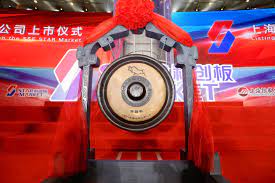

Once ready, many companies aim to either get listed on NASDAQ or the domestic Star Market stock exchange in Shanghai. However, a flurry of companies attempting to list on the latter have recently been forced to cancel their plans following increased scrutiny of the tech sector by regulators.

An interesting side effect of China’s tech growth has been a shift in the country’s attitude to risk-taking. The country has traditionally been viewed as a risk-averse society, driven by Confucian values, a focus on job security and making savings.

However, this is rapidly changing among the younger generations, who are unafraid of taking on new challenges and confronting failure. Driven by a highly competitive landscape, entrepreneurs take prompt actions from idea phase and experiment with innovative concepts immediately in the market.

“Here in China, many are willing to take high risks and live their entrepreneur dream to the fullest. They are working with a ‘try fast and fail fast’ mindset, and function within a more flexible legal environment than in the West in terms of data privacy and security,” said Charles Bark, CEO of Hinounou, a digital healthcare platform trying to help seniors live healthier lives.